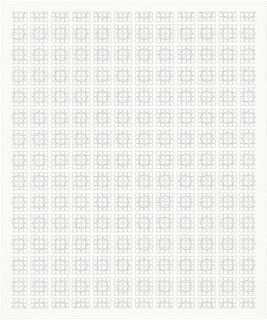

Untitled (Fra Giocondo 1511), 2010

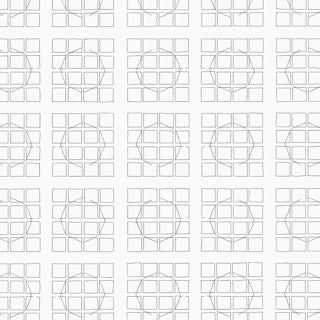

Detail Untitled (Fra Giocondo 1511), 2010

The 16 large-format drawings in the series are based on ideas developed in the form of diagrams and sketches from various eras of urban planning. They draw on urban planning models from around 33 BC as well as from the 19th and 20th centuries, which, in their respective times, represented ideal visions of urban space. These concepts aimed to eliminate the uncontrollable and random aspects of urban environments and instead impose a structured order. In the drawings, each of these original diagrams is mirrored along both the horizontal and vertical axes, creating a repeated pattern. The formalism already inherent in the original sketches is transformed into a systematic, repeatedly reproduced motif within the drawings. From this strict, authoritarian order emerges an even, all-over pattern that both reflects and dissolves the rigid regularity of historical urban planning ideals.

Wilhelmshaven, Heusenstamm, Bruchsal, Aalen, Mainz, Forchheim, Wolfsburg – these are not necessarily cities that elicit swooning, yet nonetheless these are the cities whose websites result from a Google search for Stadtleitbilder [urban models]. One hesitates to think about how this list of results might expand with an extended search. All these cities, according to the impression given… read more

Wilhelmshaven, Heusenstamm, Bruchsal, Aalen, Mainz, Forchheim, Wolfsburg – these are not necessarily cities that elicit swooning, yet nonetheless these are the cities whose websites result from a Google search for Stadtleitbilder [urban models]. One hesitates to think about how this list of results might expand with an extended search. All these cities, according to the impression given by their efforts at self-promotion, can not get along without Leitbilder. We can understand these models to include the consideration of the citizens’ interests, the city’s history, and the heterogeneity of its present life. The idea of all this is to show the path to an attractive future. Fine, but promoting a Stadtleitbild is at the same time one aspect in the performance of a showcase – a display window, which surrenders itself to desire in order to stave off the sheer contingency of the cityscape by means of an orderly totality. We might confront this desire with Adorno’s line, »If you cry for Leitbilder, they have already become impossible.« According to his diagnosis in the essay »Ohne Leitbild« from 1960, Leitbilder represent »the weakness of their subjectivity [ihres Ichs] vis-á-vis circumstances about which they claim to be able to do nothing, and the blind power of the once in this way existing [des einmal so Seienden].«2 The blind power of the once existing – this impression cannot be dismissed if one is to make a futile attempt to flaneur through these cities that prop themselves up with a Leitbild.

There is a utopian dimension to this self-presentation, characteristic of Stadtleitbilder since their origins in the 19th century, when cities underwent massive changes through industrialization and immigration. These challenges were met with an offence of theories, which Michel de Certeau has termed, »the transformation of the urban fact into the concept of the city.«3 The combination of utopia and urbanism is evident in the Stadtleitbilder of the Berlin urban planner James Hobrecht, as well as in those of Frank Lloyd Wright and Le Corbusier. These proposals have been taken up in Herbert Stattler’s drawing cycle »Stadtleitbilder«, in which the utopianism of urban models is traced back to the ideal forms of platonic bodies. In a conversation in Arcadia with the omnipresent Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Stattler referred to Plato and his praise of mathematicians: »They substitute objects for imagined mathematical forms, which they see as ideals in opposition to objects themselves. He describes these ideal three dimensional bodies, known as platonic bodies, as a beautiful whole, contained and ordered within itself. And exactly this ›beauty‹ and this thinking in figures is also found in the myriad representations of the idea of the city. The basic mathematical forms like the circle, square, or triangle thread through all of these visualizations of city planning, and yet this formalism contains the danger of becoming pure decoration.«

Here critique is not focused on the often articulated failure of utopia in the face of sprawling (or dwindling) urban areas, but rather on the iconic and above all mathematical ideal which finds expression in these plans. Both the allure and the risk of this critique crystalizes thus in the picture, rather than the word. Ornament and decoration have been frequently set aside for copious verbal criticism, but what should the pictures look like in which this criticism occurs? Is there not a danger connected with such an idea, that the picture will succumb to decoration? Not necessarily. Decoration, to draw once again on Adorno, is nothing more than a weakness vis-a-vis circumstances, about which one is no longer capable of doing anything. It is exactly this consensus about what cannot be changed, only that it comes from a mode of formalism and beautification. In contrast, Adorno develops a conception of art, which rejects the decorative status of this consensus. According to this conception, it is a trivializing idea that great artworks of the past are »locked (in it) and are identical with its (the past’s) language.«4 Art must not conform entirely to the style, the time period, or the order, in which they actually originate. It is not enough that it serves as the representative of some generality; it may constitute itself through contact with this, but it is constantly concerned with not letting contact spill over into assimilation or fusion. For this reason, Adorno argues, that meaningful artworks represent »force fields« »in which a conflict is carried out between the ordered norm and that which seeks for expression« in these works.5

The term »force field« fits the cycle Stadtleitbilder because in the work a conflict emerges between the model – that is between each selected Stadtleitbild – and the reproduction of elements into a picture that reaches out beyond the canvas. This process occurs by relatively simple means: »For each (drawing) I take a Stadtleitbild and mirror it multiple times along the horizontal and vertical axes, so that each is amplified into a design. In this way the formalism of the original sketch transforms in the drawings into a repeating pattern, and thus the ornament is reproduced into a design, and thereby into decoration.« Turning, mirroring, reproducing – these techniques have been available since before Andy Warhol or Sigmar Polke. Typically these techniques are the products of print technology and therefore of automated seriality. In contrast, the Stadtleitbilder are drawn entirely by hand with pencil. This practice articulates the potential for conflict. This is not about an artistic proof that through hard and diligent work mechanized processes can be infallibly imitated. Neither is it only about a graphic commentary on the urban concept to which it is connected, but rather it is about the habile play with those techniques that typically serve the purposes of reproduction.

If multiplication by mirroring went through a playful moment in earlier periods, given that optical media and technologies were able to surprise the viewer with the magical effects of their physical precision, this moment has slowly dissipated in seriality. With his decision to employ the oldest drawing techniques, Herbert Stattler summons up exactly the force field, which conjures critique in the image – however subtle – and at the same time makes room for that which – with Adornos somewhat auratic words – »seeks for expression.« The point is that the one (i. e. critique) does not silence the other (i. e. what seeks for expression). Here art distinguishes itself from ordinary critique or from the performance of illusion.

An image doesn’t reveal whether the hand which created it has been employed as a »mere reduction machine«, in order to evoke the strictness of imitation, or whether it has been employed to conjure »a substance, a body, an organizational structure« (Henri Focillon). Stattler’s images are thus not just about Stadtleitbilder, but also about the spread of the hand, and both are revealed only in connection with each other. Focillon once remarked that the hand discovers »unbelievable adventures in material. It is never enough for it to take what is there, but rather it must work on that which is not there.«6 The same applies to its manipulation of form, pattern, and ornament. In this, the foundational elements of the Stadtleitbilder are laid bare with precision: platonic bodies signal an empire of boredom in urban planning, but this only becomes truly evident in the tactile search for an image that doesn’t need to be a Leitbild.

Translated by Alice M. Goff